Author: Heidi Jeter

Watershed Game Makes Water Science Fun for Students and Educators

On a bitterly cold morning in January, teachers and educators from around northeast Wisconsin gathered at Barkhausen Waterfowl Preserve to learn how to play and teach the Sea Grant Watershed Game.

The interactive board game helps students and local leaders understand the connection between land use and water quality. Through a series of active, hands-on simulations, participants learn how land-use decisions impact water quality and natural resources. The game is used in more than 15 states across the country.

The workshop, which was organized by UW-Green Bay, focused on the Stream Model version of the game. Kathy Biernat, owner of Zanilu Educational Services, and Anne Moser, senior special librarian and education coordinator at Wisconsin Sea Grant, introduced the watershed concept through a fun version of “three truths and a lie” about watersheds. They then walked through lesson plans and stewardship concepts to accompany the Watershed Game.

To play, the educators divided into groups, with each group representing a community they that needs to reduce excess phosphorus runoff. They debated land-use decisions, the costs and benefits of implementing land-use changes, and the trade-offs of various flood resiliency actions for their community.

After a spirited game, Biernat and Moser led educators through a discussion of how they might implement the Stream Model into their classrooms and educational venues. They also discussed other classrooms activities that would support lessons around nonpoint source pollution and community decision-making for water quality. Each educator took home a Stream Game and lesson plans for implementing the activity in their school.

Logan Lassee, an assistant naturalist at Brown County Parks Department, plans to incorporate the game into a recycling program for fifth and sixth graders.

“The workshop was an exciting event where there was collaboration amongst educators from many different areas of education,” he says. “I personally thought this game was a very fun and a realistic approach to understanding how land and water use can affect the ecosystem on a larger scale.”

Andrea Stromeyer, the education programs coordinator at the Door County Maritime Museum, is familiar with watersheds but new to bringing STEM programming to a history museum. She appreciates the framework the game provides.

“This game touches on points about land management surrounding watersheds that I didn’t previously think to add into my classroom discussions,” she says. “I especially love how I can scaffold this up or down depending on the ages of students and sizes of classes.”

Stromeyer plans to incorporate the game into Great Lakes Literacy-based programs this summer. She and her colleagues have also been thinking about interesting expansion ideas relevant to their specific Door County area.

“I’m thankful to the Freshwater Collaborative and the other hosts of this workshop for supporting Wisconsin educators by providing us copies of the game,” she adds.

This workshop was primarily sponsored by the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin with support from Wisconsin Sea Grant. Emily Tyner and Lynn Terrien at UW-Green Bay planned and organized the workshop as part of a Freshwater Collaborative–supported grant. Learn more about UW-Green Bay’s Educators and Students Rise to Freshwater Challenges programs at www.uwgb.edu/freshwater-collaborative.

Check Out Summer Course Offerings

Enrollment is open for summer Freshwater Collaborative courses! Details at https://freshwater.wisconsin.edu/for-students/fcw-courses-experiences/

UWO Students Conduct R&D for Wisconsin-based Whirl-Pak

Water research can result in a lot of plastic waste. High-quality sample collection — such as that for researching emerging contaminants like perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — requires sterilized containers that, unfortunately, can’t be reused or even recycled in most cases.

Is there an economical and efficient way to reduce the waste?

Product engineers at Whirl-Pak, Filtration Group, a Wisconsin-based company that makes secure sampling bags, think there is, and they’ve tapped students and faculty at UW Oshkosh to help.

Whirl-Pak is well-known in the dairy industry, having developed a process called the universal sampling procedure to help ensure milk quality. The company branched into the water industry in 1981 and has seen significant success in the United Kingdom with replacing conventional rigid sampling bottles with their flexible bags, which require less plastic, water and emissions to produce and ship. To grow their business in the United States, they wanted to identify a lab that was processing large quantities of water samples.

When a company representative asked the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin for help, Marissa Jablonski, executive director, immediately thought of UW Oshkosh’s Environmental Research and Innovation Center (ERIC). The state-certified laboratory hires students to provide well water testing and bacteriological and chemical analysis for water systems.

The connection has resulted in a university-industry partnership that provides valuable work experience for students, helps solve a business challenge and may reduce plastic pollution. It’s a win-win-win project that exemplifies how academia and industry can work together.

Their efforts are being supported by the Water Enterprise Program at UW Oshkosh, which connects university researchers and students with industry partners to address issues important to those partners. The program is part of the suite of projects at UW Oshkosh funded by the Freshwater Collaborative. It allows faculty and academic staff to request a mini grant (up to $15,000) to work on an innovative project with an external partner. The projects must also include student researchers.

Carmen Ebert, associate lab director for ERIC lab, submitted a request in 2022 to conduct initial research and development on Whirl-Pak products.

“This was an opportunity to jumpstart the project with Whirl-Pak,” she says. “We looked at the feasibility of using their bags for collection as well as incubation of samples in the lab. We then inoculated the bags with known organisms and compared the bags to known methods of collection.”

Once they proved Whirl-Pak bags could be used to sample effectively and that samplers liked using them, Cherelle Bishop, Whirl-Pak’s product engineering manager, wanted to develop a more targeted case study. Bishop wants to gather data to show potential customers that their sampling bags work just as well as conventional containers — and have the added benefits of reducing plastic waste and the storage space required for collection containers.

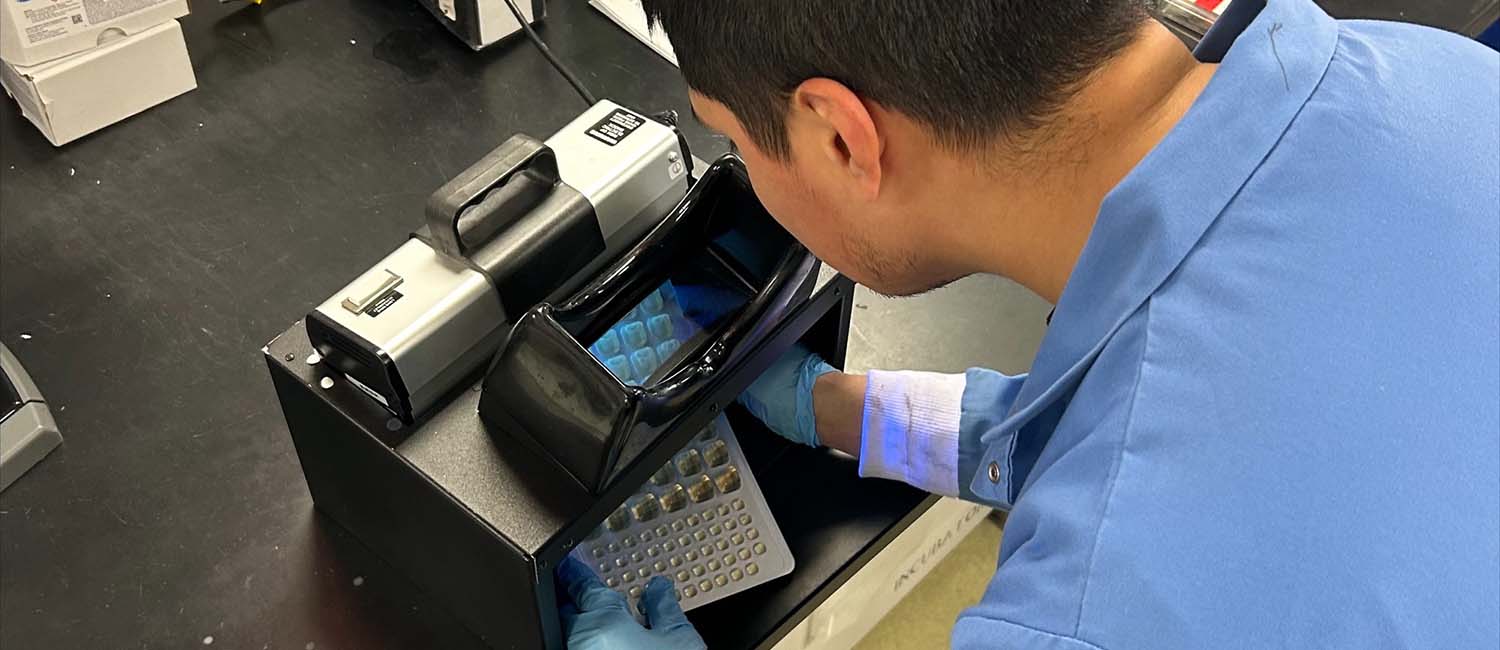

She and Ebert received a second mini grant from the Water Enterprise Program in 2023 to conduct more in-depth testing of the bags and their ability to sample surface and well water. Students conduct the lab testing and analysis under the guidance of ERIC staff. Erick Carranza, a UW Oshkosh graduate student, says working on the project has increased his familiarity with methods of detecting bacteria.

“My favorite part of this project has been being exposed to a new form of detection for coliform bacteria and E. coli,” he says. “I had never used the standard method of detection prior to working at the ERIC lab, and now learning the Whirl-Pak method for the same purpose is exciting.”

The partnership goes beyond R&D. Last year, Bishop was invited to the Great Lakes Beach Association Conference, which was hosted by UW Oshkosh, and the Freshwater Collaborative’s FresH2O Partner event. Both events provided her with opportunities to meet more people working in the water sector and learn what’s important to them. She also visited UW Oshkosh to meet students and see firsthand some of the other research taking place. She sees the partnership as mutually beneficial.

“UW Oshkosh is a Wisconsin-based university and we’re a Wisconsin-based company. We want stronger ties with the UW System,” she says. “We wanted to craft something that was exciting for both of us. There’s engagement and momentum and that can only bring good things to both sides.”

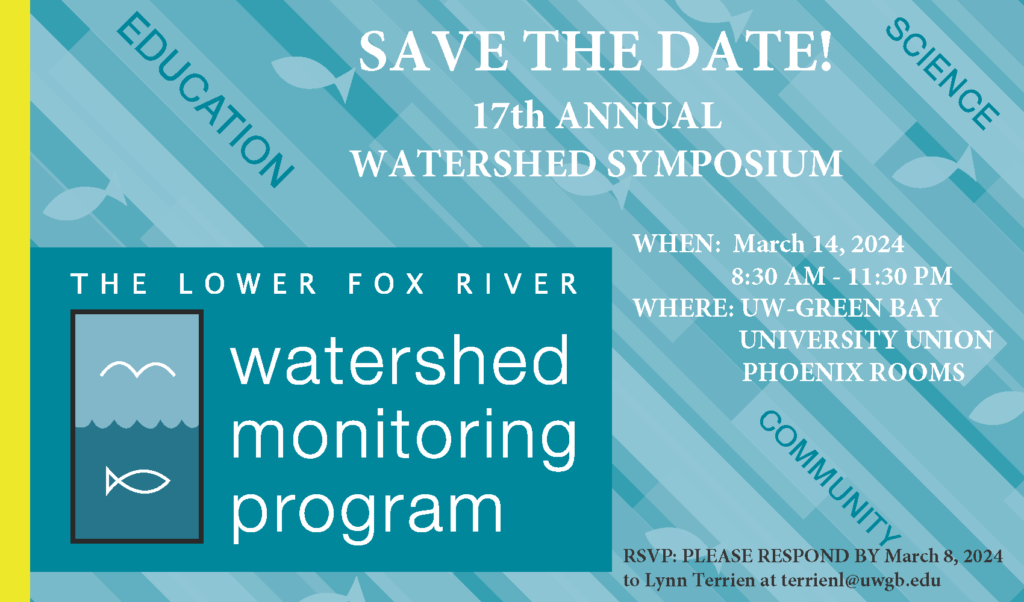

17th Annual Watershed Symposium at UW-Green Bay, March 14

Undergraduate students and high school students and teachers will share their experiences participating in the the Lower Fox River Watershed Monitoring Program.

The event is part of UW-Green Bay’s Educators and Students Rise to Freshwater Challenges grant from the Freshwater Collaborative. Read more about last year’s event.

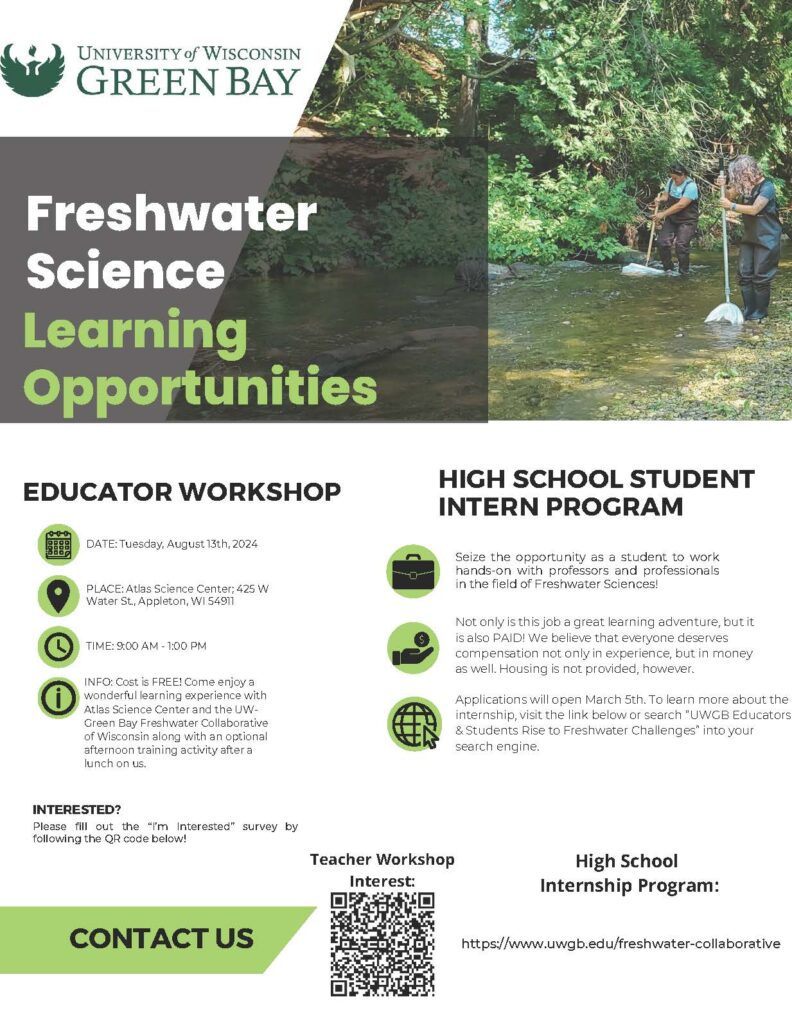

Freshwater Science K-12 Educator Workshop, Aug. 13

UW-Green Bay is hosting a free freshwater science workshop for K-12 educators and optional training activity at the Atlas Science Center in Appleton. This event is supported through the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin.

Building a Better Response to PFAS Contamination

A career in water or the environment never occurred to AJ Jeninga until she took a winter break course to Yellowstone as an undergraduate. Now a double alumna of the Universities of Wisconsin, Jeninga was hired as the first-ever emerging contaminant outreach specialist at the University of Wisconsin – Extension’s Natural Resources Institute. She works with the community and local health departments to build a better response to PFAS contamination.

“Most of my projects are water-related because that’s my background,” she says, “and most of my focus is on creating partnerships and providing support for people working on emerging contaminants.”

The new position was created in response to the growing number of questions and concerns about PFAS that Extension was receiving from community members throughout the state. Jeninga’s combination of research and outreach experience helped her stand out in the hiring process.

“AJ was an excellent candidate with a great blend of applicable research skills and experience working with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services,” says Chad Cook, Jeninga’s supervisor and Extension’s associate director of outreach. “Her research provided a strong foundation in understanding not only PFAS but other emerging contaminants and gave her the skills and confidence to interpret and share technical research with non-technical audiences.”

Jeninga credits her faculty mentors at UW-Whitewater and UW-La Crosse for inspiring her passion for water advocacy and providing opportunities that prepared her for her current position.

“I worked with a lot of different people through my research projects. I developed my people skills and figured out people’s work styles,” she says. “And the most important skill I acquired as a student was the ability to break down research and make it accessible for people who aren’t toxicologists or researchers.”

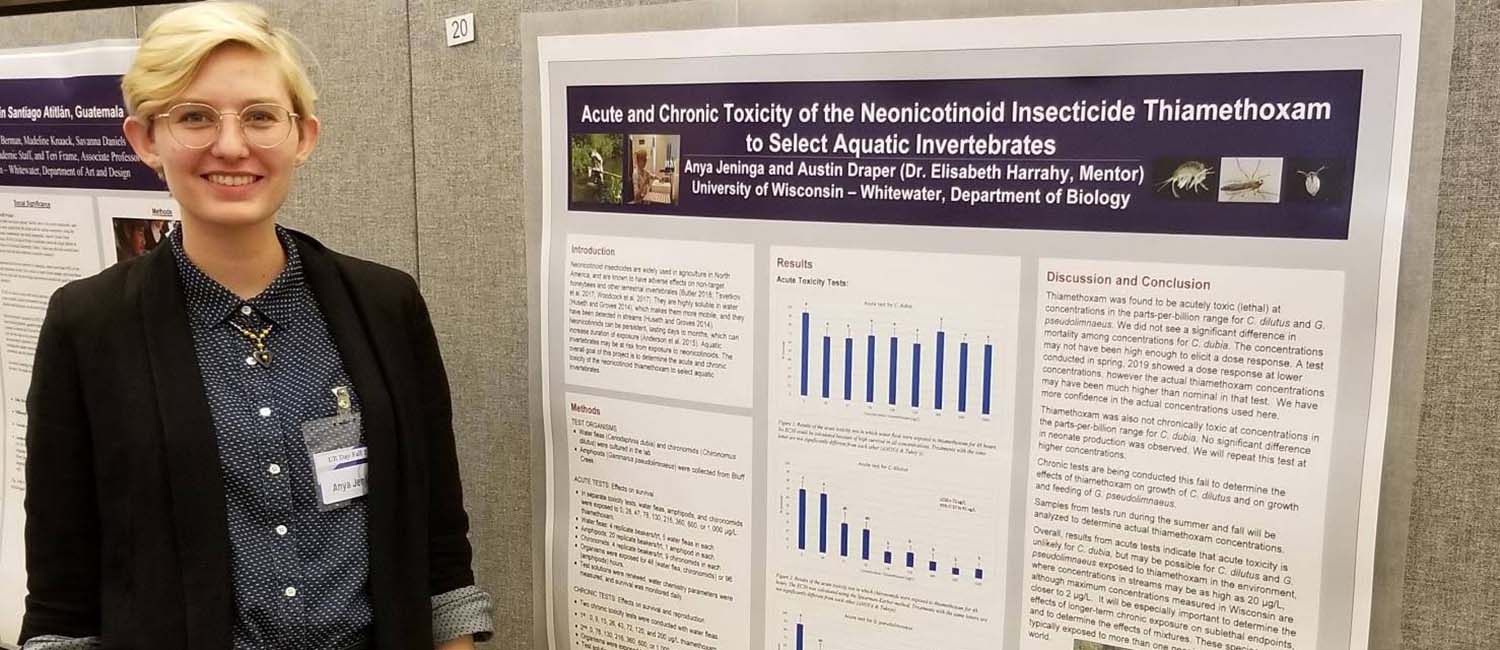

The Delavan native originally enrolled at UW-Whitewater as a pre-med biology major, but after Yellowstone, she switched to an environmental track. She took ecology and environmental toxicology with Professor Elisabeth Harrahy, and then joined Harrahy’s lab as an undergraduate researcher on one of the first projects funded by the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin.

Harrahy was collaborating with Professor Tisha King-Heiden at UW-La Crosse to look at the effects of two common pesticides on aquatic species. Harrahy’s lab was studying the effects of thiamethoxam and imidacloprid on invertebrates, while King-Heiden was studying their effects on fish.

“I got to do field work, which I had not had the opportunity to do up until that point, and I learned a lot about lab practices,” Jeninga says.

Jeninga’s research experience was cut short due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but after graduation in May 2020, she enrolled in graduate school at UW-La Crosse to work on King-Heiden’s fish research. She had the opportunity to give back by mentoring new undergraduates who were being funded by the Freshwater Collaborative.

During that time, she presented her research at the Mississippi River Research Consortium and the Midwest Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) Conference, where she won an award for best student poster, and the North American SETAC Conference. Jeninga’s thesis work on the adverse effects of imidacloprid on fathead minnows was published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry in 2023.

Her time in graduate school also connected her to staff at the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene, with whom she worked closely. Those connections helped her land a one-year Water Resources Policy Fellowship with Wisconsin Sea Grant, during which time she switched her focus to PFAS in groundwater. The fellowship prepared her to take on her challenging new role.

“AJ’s combination of research and translation/outreach fit perfectly into what we were looking for,” Cook says. “Our position is a new one that we are defining as we go so AJ’s ability to work in somewhat nebulous conditions without clear outcomes is an asset as, together, we can figure out how this position can best support PFAS efforts across the state.”

As a Wisconsinite, Jeninga is proud to live in a state that is taking a lead role on PFAS research. The more she learns about emerging contaminants, the more passionate she feels about her work.

She’s already created a step-by-step guide that helps citizens interpret their private well water reports and provides resources so they know how to advocate for themselves if their wells are contaminated. Another project is a story map that will look at PFAS research in Wisconsin and focuses on people who’ve been affected. A long-term goal is to help create a standardized response to PFAS contamination.

“I like talking to homeowners and others about PFAS. It’s incredibly intimidating and complicated, and we need community partnerships to make change,” she says. “I think it’s really cool that Wisconsin has dedicated so many resources to PFAS.”