A career in water or the environment never occurred to AJ Jeninga until she took a winter break course to Yellowstone as an undergraduate. Now a double alumna of the Universities of Wisconsin, Jeninga was hired as the first-ever emerging contaminant outreach specialist at the University of Wisconsin – Extension’s Natural Resources Institute. She works with the community and local health departments to build a better response to PFAS contamination.

“Most of my projects are water-related because that’s my background,” she says, “and most of my focus is on creating partnerships and providing support for people working on emerging contaminants.”

The new position was created in response to the growing number of questions and concerns about PFAS that Extension was receiving from community members throughout the state. Jeninga’s combination of research and outreach experience helped her stand out in the hiring process.

“AJ was an excellent candidate with a great blend of applicable research skills and experience working with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services,” says Chad Cook, Jeninga’s supervisor and Extension’s associate director of outreach. “Her research provided a strong foundation in understanding not only PFAS but other emerging contaminants and gave her the skills and confidence to interpret and share technical research with non-technical audiences.”

Jeninga credits her faculty mentors at UW-Whitewater and UW-La Crosse for inspiring her passion for water advocacy and providing opportunities that prepared her for her current position.

“I worked with a lot of different people through my research projects. I developed my people skills and figured out people’s work styles,” she says. “And the most important skill I acquired as a student was the ability to break down research and make it accessible for people who aren’t toxicologists or researchers.”

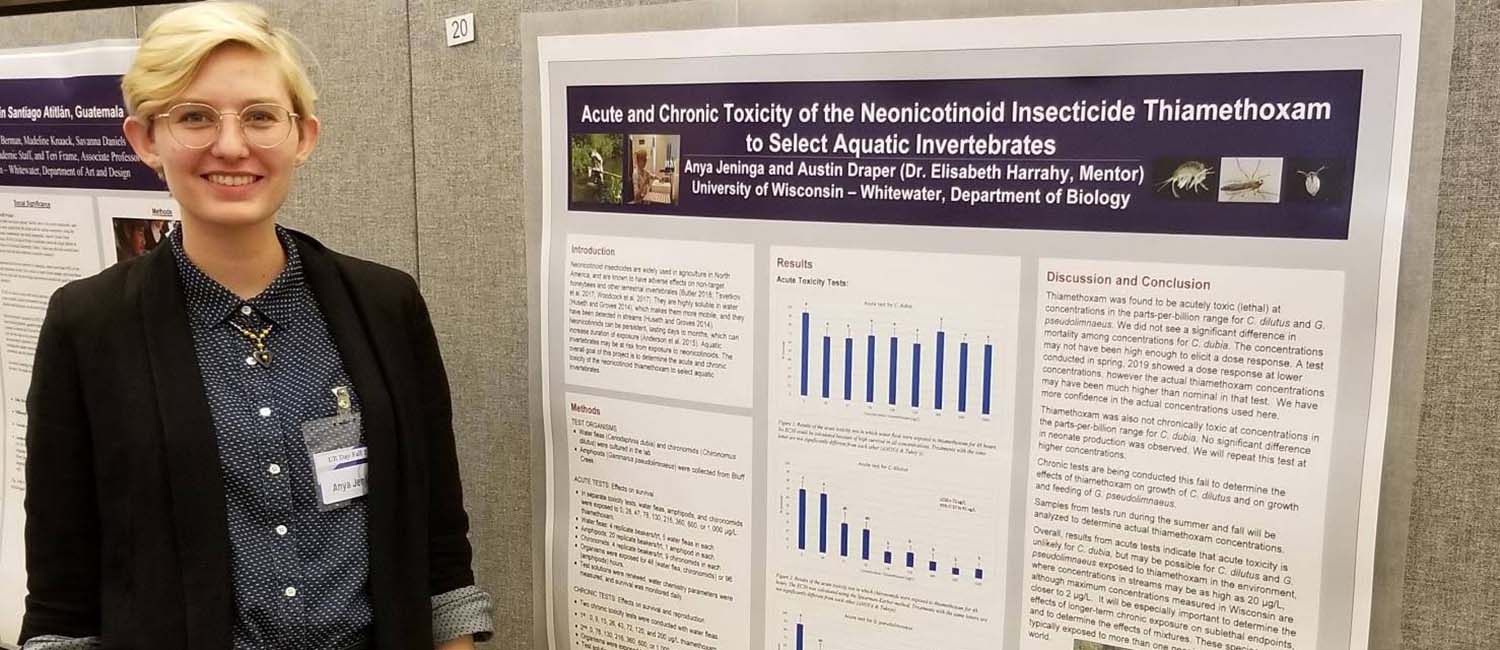

The Delavan native originally enrolled at UW-Whitewater as a pre-med biology major, but after Yellowstone, she switched to an environmental track. She took ecology and environmental toxicology with Professor Elisabeth Harrahy, and then joined Harrahy’s lab as an undergraduate researcher on one of the first projects funded by the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin.

Harrahy was collaborating with Professor Tisha King-Heiden at UW-La Crosse to look at the effects of two common pesticides on aquatic species. Harrahy’s lab was studying the effects of thiamethoxam and imidacloprid on invertebrates, while King-Heiden was studying their effects on fish.

“I got to do field work, which I had not had the opportunity to do up until that point, and I learned a lot about lab practices,” Jeninga says.

Jeninga’s research experience was cut short due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but after graduation in May 2020, she enrolled in graduate school at UW-La Crosse to work on King-Heiden’s fish research. She had the opportunity to give back by mentoring new undergraduates who were being funded by the Freshwater Collaborative.

During that time, she presented her research at the Mississippi River Research Consortium and the Midwest Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) Conference, where she won an award for best student poster, and the North American SETAC Conference. Jeninga’s thesis work on the adverse effects of imidacloprid on fathead minnows was published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry in 2023.

Her time in graduate school also connected her to staff at the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene, with whom she worked closely. Those connections helped her land a one-year Water Resources Policy Fellowship with Wisconsin Sea Grant, during which time she switched her focus to PFAS in groundwater. The fellowship prepared her to take on her challenging new role.

“AJ’s combination of research and translation/outreach fit perfectly into what we were looking for,” Cook says. “Our position is a new one that we are defining as we go so AJ’s ability to work in somewhat nebulous conditions without clear outcomes is an asset as, together, we can figure out how this position can best support PFAS efforts across the state.”

As a Wisconsinite, Jeninga is proud to live in a state that is taking a lead role on PFAS research. The more she learns about emerging contaminants, the more passionate she feels about her work.

She’s already created a step-by-step guide that helps citizens interpret their private well water reports and provides resources so they know how to advocate for themselves if their wells are contaminated. Another project is a story map that will look at PFAS research in Wisconsin and focuses on people who’ve been affected. A long-term goal is to help create a standardized response to PFAS contamination.

“I like talking to homeowners and others about PFAS. It’s incredibly intimidating and complicated, and we need community partnerships to make change,” she says. “I think it’s really cool that Wisconsin has dedicated so many resources to PFAS.”