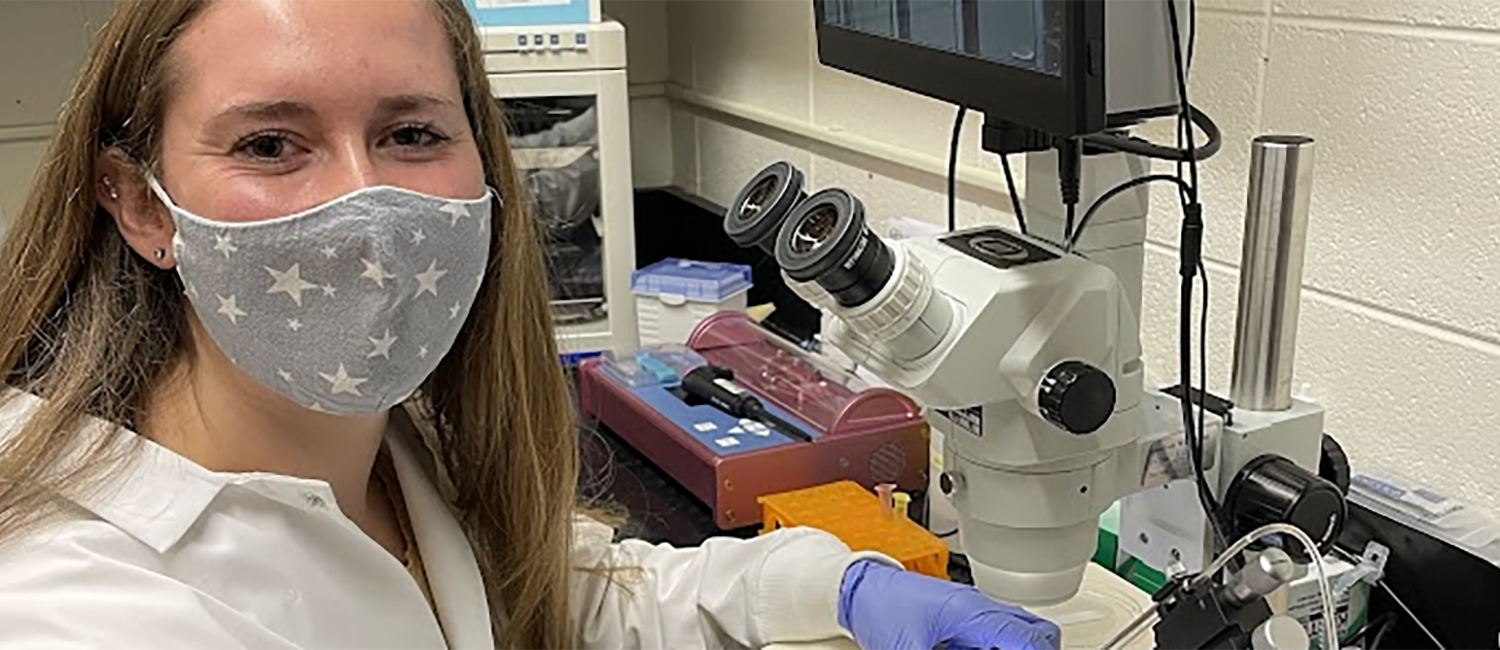

When Elizabeth Johnson, graduated with a Biology degree from the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire in May 2021, she had a big advantage in the job market. She knew how to use CRISPR, a rapidly advancing technology that can be used to edit genes.

“I’ve had many job opportunities because they see that I’ve worked with CRISPR,” says Johnson, who is now a research associate at the University of Minnesota.

Johnson entered college with plans to go to dental school. Then Brad Carter, a new assistant professor at UW-Eau Claire, came to one of her classes to talk about research opportunities in his new lab, including work with CRISPR.

Carter had received funding from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin to partner with Professor Michael Carvan at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee to use CRISPR reagents to create a zebrafish knockout line that would enable them to study the effects of methylmercury toxicity. Mercury is known to cause neurological problems in kids, and it can be found in high concentrations in Wisconsin’s fish populations. What they learn about the genetic variations that may increase sensitivity to mercury could benefit humans and fish.

“This research allows us to train students in not only working with fish but with these advanced molecular tools. They are being exposed to things that will definitely carry them forward,” Carvan says. “And they’ve been working with fish, so they will have a fondness for getting into opportunities that are freshwater-related.”

Johnson was the first student hired to work on the project. She set up the protocols, created standard operating procedures and learned how to synthesize RNA molecules using CRISPR. She initially disabled a pigmentation gene so they could see that the technique worked. Then she began looking at genes linked to mercury toxicity.

“I would recommend every student gets to try research,” says Johnson, who intends to go to graduate school in the future. “It’s easy to assume things in class. When you get to do hands-on research and see what the field is like, it’s a totally different experience.”

Part of her job in the lab was to train her successor Ashley Lutzke, who is continuing to test the mercury genes in the zebrafish. Working on the project changed Lutzke’s career plans as well. As a freshman, she chose a Psychology major and was considering a career as a genetics counselor. She added a Biology major after taking a foundational biology class and then applied for the position in Carter’s lab. When she graduates in May 2022, she plans to head to graduate school.

“After working in the research lab, I realized how much I liked the science part of it. It confirmed I want to go into research, work in a lab and go to graduate school to get my PhD,” Lutzke says. “This opportunity has changed my whole outlook for the better. I can’t imagine how different my career plans would be. I’m really grateful for the opportunity it provided.”

Despite COVID restrictions, the students often collaborated, sometimes relying on FaceTime and texting to communicate. They had regular virtual meetings with Carter and Carvan, who provided mentorship. And they both presented their research at regional conferences.

Not only did the funding provide hands-on technical training for two students, but the Freshwater Collaborative grant created a collaboration between an established freshwater researcher and a new tenure-track faculty member.

“One of the wonderful things about our CRISPR project is the Freshwater Collaborative funding really enabled our original collaboration in terms of research and resources. It’s been a really meaningful and substantial kickstart to our work together,” Carter says. “Our progress has me excited to continue collaborating on research into the future.”